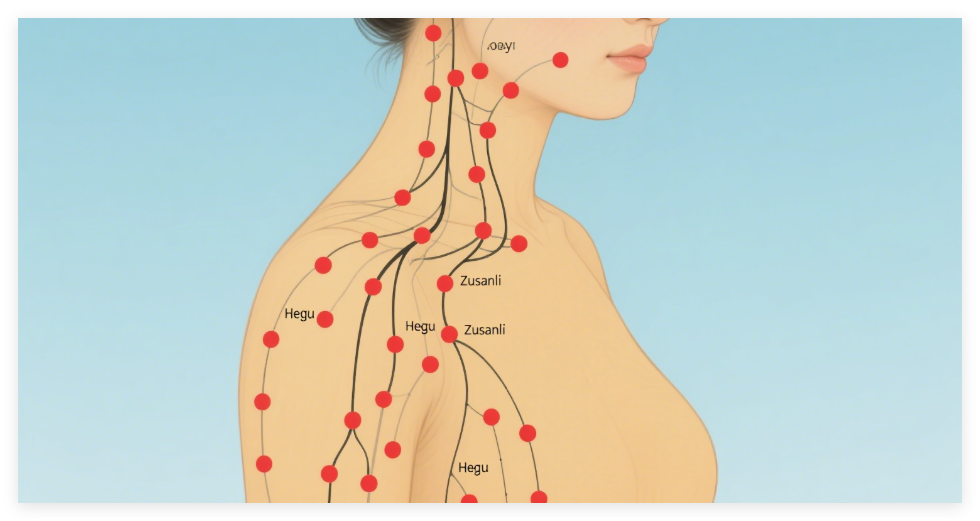

Acupoint location has traditionally been understood as more than the tiny needle-point areas commonly depicted in modern textbooks and acupuncture charts. While contemporary educational materials often present these points with remarkable precision – describing exact positions relative to bones, muscles, blood vessels, and nerves measured in specific distances – the reality of acupoint positioning is far more nuanced and dynamic than these static representations suggest.

The Evolution of Acupoint Understanding

The precision we see in modern acupuncture charts results from centuries of accumulated clinical data – what we might call “big data” in today’s terminology. Ancient Chinese medical practitioners discovered through extensive practice that most body points exhibit sensitivity characteristics such as soreness, numbness, distension, or pain when pressed. Over generations of clinical observation, these points were found to occupy relatively stable positions in healthy individuals.

Consider the famous Zusanli (ST36) acupoint, located on the lateral side of the lower leg, three finger-widths below the knee cap. Modern descriptions place it precisely along the line connecting the lateral knee depression to the ankle, with specific anatomical references to the lateral cutaneous nerve of the calf and branches of the anterior tibial vessels. This detailed mapping represents the integration of traditional Chinese medicine with Western anatomical knowledge.

However, this precise description doesn’t necessarily translate to exact accuracy for every individual, as Traditional Chinese Medicine emphasizes personalized treatment approaches.

The Concept of “Zhong” (Balance) in Acupoint Location

The term “Chinese Medicine” derives its significance from the character “zhong” (中), meaning balance or center. This represents the fundamental principle of yin-yang balance – the harmonious state that all TCM treatments aim to achieve. When the body maintains this balanced state, acupoints typically reside in their textbook locations.

When illness or imbalance occurs, representing a disruption of yin-yang harmony, acupoints may shift slightly from their standard positions – moving up, down, left, or right. The practitioner’s skill lies in identifying the most sensitive spot within the general acupoint area, as this represents the true therapeutic location for that specific moment and individual.

[Image placeholder: Diagram showing acupoint regions rather than fixed points on human body]

Alt text: Acupoint regions and zones for precise traditional Chinese medicine treatment

Understanding Acupoints as Dynamic Regions

Rather than fixed points, acupoints function more accurately as therapeutic zones or regions. The most effective treatment location within this zone changes constantly, responding to the patient’s breathing, pulse, and overall physiological state. This dynamic nature requires practitioners to locate the most sensitive spot within the general acupoint area through careful palpation and patient feedback.

For more insights on personalized TCM approaches, explore our comprehensive guide on Chinese Medicine Tips for Healthy Living.

Clinical Methods for Acupoint Location

Traditional Chinese Medicine employs three primary methods for acupoint positioning:

Bone Measurement Method (Gu Du Zhe Liang Fa)

This technique divides body parts into equal segments, with each segment representing one “cun” (Chinese inch). For example, the distance from the outer knee depression to the outer ankle midpoint equals 16 cun, allowing practitioners to locate Zusanli at 3 cun below the knee and Shangjuxu at 6 cun below.

Body Landmark Method (Ti Biao Biao Zhi Fa)

This approach uses anatomical features like eyebrows, nipples, navel, bone joints, and muscle prominences as reference points. The Yintang point lies between the eyebrows, while Danzhong sits at the midpoint between the nipples.

Finger Measurement Method (Shou Zhi Bi Liang Fa)

This method uses the patient’s own finger measurements as units. The middle finger’s middle joint width (when bent) equals one cun, the thumb joint width also equals one cun, and four fingers together measure three cun. Importantly, measurements should always use the patient’s finger proportions, not the practitioner’s.

Learn more about Herbal Medicine combinations that work synergistically with proper acupoint stimulation.

Identifying Active Acupoints

Practitioners recognize active acupoints through several clinical signs:

Pressure sensitivity and tenderness, hardened nodules or tissue changes, heightened skin sensitivity to light stimulation, color changes or pigmentation differences, and temperature variations in the surrounding tissue. These reactions serve as crucial indicators of therapeutically active points.

[Image placeholder: Close-up of practitioner’s hands examining acupoint sensitivity]

Alt text: Skilled hands examining acupoint sensitivity for effective natural healing treatment

Clinical Application Principles

Effective acupoint location requires understanding that acupoints connect deeply with internal organs and systems through bidirectional communication pathways. From internal to external, they reflect pathological conditions; from external to internal, they receive therapeutic stimulation for disease prevention and treatment.

Professional practitioners combine measurement methods while considering patient positioning, posture, and cross-referencing with surrounding anatomical landmarks. The governing and conception vessels along the body’s midline provide reliable reference points for locating bilateral acupoints.

For those interested in movement-based healing approaches, discover our guide to Tai Chi and Qi Gong practices that complement acupoint therapy.

Successful acupoint therapy requires recognizing that these points exist on living, breathing individuals whose physiological states constantly change. The most effective treatment occurs when practitioners adapt their techniques to locate the most therapeutically active points within traditional acupoint regions, rather than relying solely on static anatomical references.

This dynamic understanding of acupoint location represents the essence of traditional Chinese medicine’s personalized, patient-centered approach to healing and wellness.