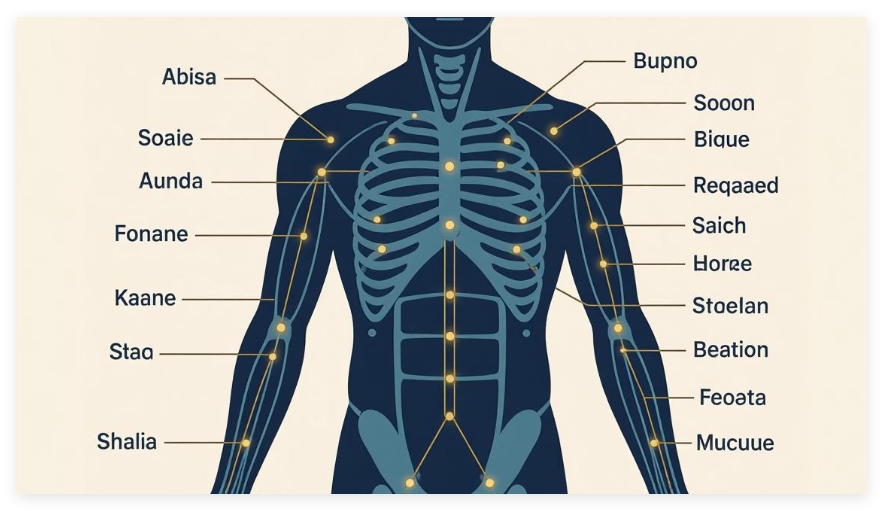

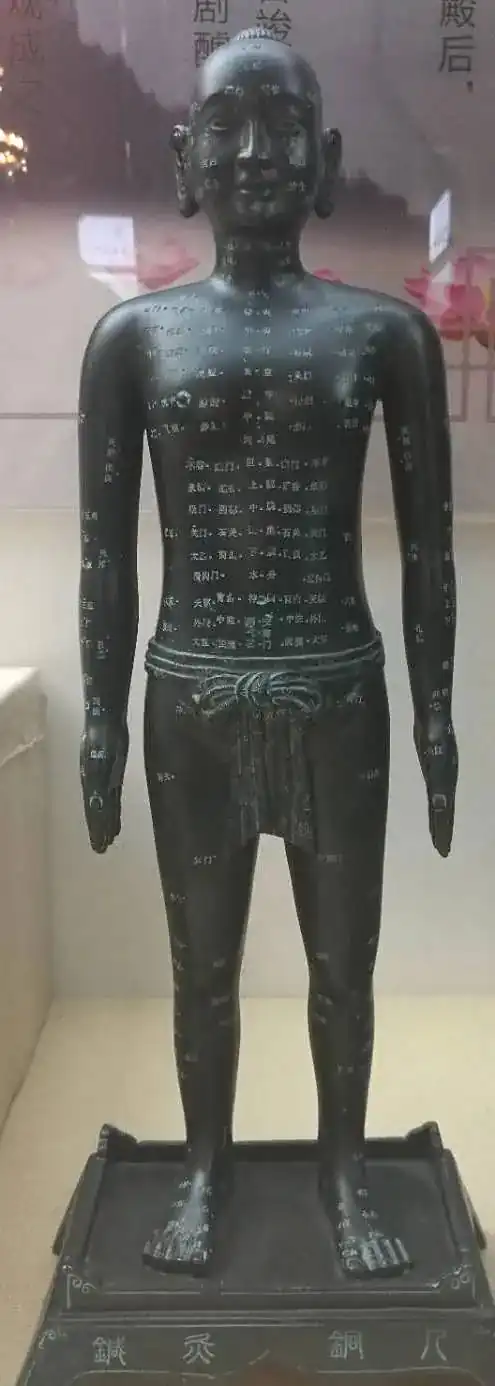

Acupoints, also known as acupuncture points (pronounced “shù” in Chinese), are special locations on the human body where the qi (vital energy) and blood of organs and meridians flow in and out. These points serve as the primary treatment sites for acupuncture, massage therapy, and other traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) practices. Most acupoints are located where nerve endings are densely concentrated or where larger nerve fibers pass through. They are also referred to as “holes,” “points,” or “pathways” in traditional terminology.

What Exactly Are Acupoints?

The term “acupoint” literally means “hole position” in Chinese. The word “acu” refers to holes or cavities, while “point” indicates location. Therefore, acupoints represent specific positions of holes or cavities on the human body. These points are typically located beneath the skin’s surface, nestled within the spaces and gaps between muscles, bones, and fascia. In other words, they are not easily visible or exposed in obvious locations on the body’s surface.

But what is the true nature of acupoints? Are they genuinely special anatomical structures in the human body?

Scientific Exploration: The Electrical Properties of Acupoints

Many researchers have explored the essence of acupoints through their electrical characteristics. In 1950, Japanese scientist Yoshio Nakatani used 12-volt direct current through human skin and discovered certain “good conductor points” with exceptionally high electrical conductivity. Most of these points were located at or near traditional acupoints. Shortly afterward, French acupuncturist Niboyet, with the assistance of his colleagues, confirmed this phenomenon using skin resistance measurement methods. He determined that acupoints have only half the electrical resistance of the surrounding skin areas. Measurements conducted on cadavers yielded similar results.

Nakatani observed that these good conductor points appeared in regular, linear arrangements on the body surface, which he termed “good conductor networks.” The pathways of these networks largely corresponded with traditional meridian routes. Nakatani believed that “good conductor points” were essentially “acupoints,” and “good conductor networks” represented the meridian system.

Since discovering the good conductor network in 1950 until 1971, Nakatani delivered over 400 academic presentations throughout Japan and published a specialized journal titled “Japanese Journal of Good Conductor Network and Autonomic Nervous System” for academic research, gaining significant international influence.

In the late 1950s, Chinese scholars conducting research on the electrophysiology of acupoints also confirmed that acupoints possess characteristics of low electrical resistance and high electrical potential.

Challenges and Limitations

However, it’s estimated that the total area of all acupoints accounts for only 0.04% of the body’s surface, while areas of low electrical resistance are numerous throughout the body, extending far beyond acupoint locations. Moreover, various factors such as eating, sleeping, physical activity, timing, seasons, temperature changes, and psychological states can all influence skin resistance values. This makes it quite difficult to accurately identify all meridian points using skin resistance measurement methods alone.

French researcher Dela Fouye spent five years applying this method to locate acupoints, but the results differed significantly from traditional Chinese acupoint locations, forcing him to abandon the research. Although good conductor points don’t perfectly align with traditional Chinese medicine acupoints, this research has promoted the development of electroacupuncture. Over the past thirty years, various “meridian measurement devices,” “acupoint detectors,” and “information diagnostic instruments” developed in China and worldwide have largely been designed based on the good conductor point principle.

International Development and Recognition

German acupuncturist R. Voll began developing a needle-free electrical stimulation therapy at acupoints in 1953, called “Electroacupuncture According to Voll” (EAV). Voll also applied good conductor point measurement to early clinical diagnosis. He established the International EAV Association and conducted multiple EAV training sessions in the United States. In recognition of his contributions, the West German President approved awarding him the Federal Cross of Merit in 1960, West Germany’s highest honor.

In 1934, Chinese researchers Tang Shicheng and colleagues published “Research on Electroacupuncture,” marking the beginning of combining acupuncture with electrical stimulation in China. This electroacupuncture therapy, which adds electrical current to needles, was widely promoted during the Cultural Revolution period.

Among the acupuncture instruments designed based on good conductor point theory, the most influential was Japan’s “Chinese Electronic Acupuncture Therapeutic Device,” launched in the early 1980s after four years of research. This device locates good conductor points on the body surface and provides low-frequency electrical pulse stimulation. They claimed this was “an epoch-making Chinese electronic acupuncture therapeutic device born from the combination of 4,000 years of acupuncture therapy with the essence of modern science—electronic technology.”

According to reports, by 1986—the sixth year of sales—the device had been sold to over 30 countries and regions worldwide, with annual sales exceeding 100,000 units at 39,800 yen per unit, bringing Japan significant prestige and foreign exchange earnings.

Modern Research Attempts

Some researchers have attempted to compare ancient acupoint theory with modern medical theories, trying to explain them using new theories and concepts. However, these efforts have largely been unsuccessful due to the enormous complexity involved.

After decades of research, scientists still hold various opinions about the specific structure and true nature of acupoints, with no definitive answer reached to date. However, one thing remains certain: stimulating acupoints on the human body can treat and prevent diseases.

This fundamental principle continues to validate the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine practices and supports the ongoing integration of ancient wisdom with modern therapeutic approaches.

References

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Acupuncture: In Depth

- PubMed: Electroacupuncture and Acupoint Electrophysiology Research

- World Health Organization. Acupuncture: Review and Analysis of Reports on Controlled Clinical Trials

- Harvard Health Publishing. Acupuncture: A Point in the Right Direction